On World Heritage Day, A Forgotten Hill Beckons: The Urgency To Preserve Uren’s Sacred Legacy

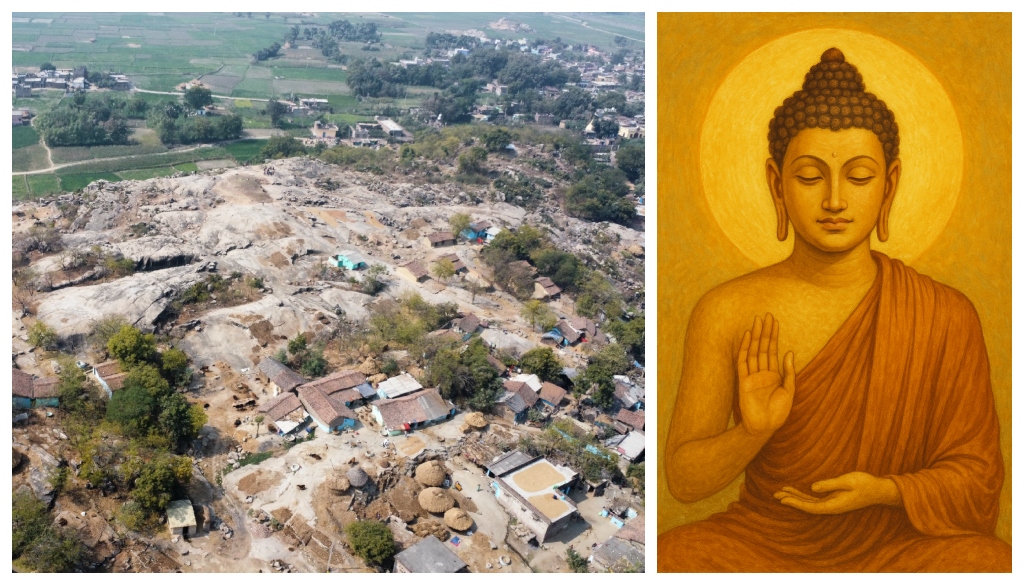

More than 1,300 years ago, Chinese monk Xuanzang recorded a hill near present-day Munger where the Buddha spent a monsoon retreat—today, that sacred mound in Uren lies forgotten and encroached. On World Heritage Day, it is time we reclaim this overlooked site not just as an archaeological remnant, but as a living chapter of India’s spiritual journey.

By Deepak Anand

On the quiet southwestern edge of Munger, atop an unassuming mound in the village of Uren, lie the whispering echoes of a sacred past. A past walked upon by none other than the Buddha himself.

On the quiet southwestern edge of Munger, atop an unassuming mound in the village of Uren, lie the whispering echoes of a sacred past. A past walked upon by none other than the Buddha himself.

More than 1,300 years ago, the renowned Chinese monk Xuanzang (Hsüen Tsang) chronicled his journey to a secluded hill near Iranaparvata—present-day Munger—where the Buddha spent one of his three-month varsas, or monsoon retreats. This was not merely a geographical note in a travelogue. It was a mark of sanctity.

In 1892, British explorer Lt. Col. Laurence Austine Waddell, working on the accounts of Xuanzang, identified this very site as the village of Uren. The coordinates are precise, the geography compelling: a mound rising 7–8 feet above fertile plains, holding within it layers of history, devotion, and loss.

Waddell was among the first to observe the Buddhist antiquities scattered across Uren—broken sculptures, engraved stupas, and sacred inscriptions. At that time, villagers recalled several “collectives” of statues. Today, only a handful remain. Even these relics, left in the open at places like Chandisthan, Mahadeosthan, and Durgasthan, are fading—eroded by nature, theft, and ignorance. Some locals, aware of the sacredness, have affixed remnants to temple walls. But most don’t know the weight of the legacy they are inheriting—or losing.

The 19th century was a turning point—not of revival but of systematic loss. As Western museums grew hungry for Buddhist art, the British administration in India obligingly supplied. Uren was not spared. Sculptures were carted away. Contractors building railway lines unearthed inscribed figures and loaded them onto freight wagons. Waddell documented one such instance where a British official removed an entire cartload from Uren in the 1850s.

This colonial loot marked the beginning. Since then, international syndicates, often working with local actors, have fuelled an underground market for antiquities. In villages like Uren, where poverty blurs the past, history is easily stolen or sold. Sacred stones are demolished as easily as granite is quarried. Xuanzang had described Chaityas and a colossal Buddha image. By the time Waddell arrived, they were gone. “Intentionally destroyed,” he concluded.

Even the sacred footprints—the very imprints of the Enlightened One—are now surrounded by encroachments: cowsheds, homes, and heaps of indifference. Dwellings have grown over survey-marked mounds. Paths the Buddha once walked for alms are now narrow lanes choked by neglect. And yet, the signs are there. Smoothened rocks, life-sized stupas, votive inscriptions—every inch of this Hill murmurs Dhamma.

But no pilgrims come. Uren remains absent from the Buddhist trail, disconnected from Bodh Gaya, Rajgir, and even Patna. It is reachable only by slow trains that stop at this forgotten outpost. A proposed expressway linking Patna to Munger via Uren brings hope, but the road to cultural salvation is longer.

This World Heritage Day, let us ask ourselves: What does it mean to protect heritage? Is it enough to display artefacts behind glass in distant museums? Or must we preserve the sacred geography where faith was once practiced under open skies?

Uren is not just another archaeological site—it is a living, breathing chapter in the journey of Buddhism. The entire Hill, not just isolated carvings, should be seen as sanctified. But before revival, there must be respect. Before tourism, preservation. The first urgent step is clear: free the Hill from encroachments. Establish a Parikrama Path—a circular pilgrimage route—around its one-kilometre perimeter. Let the community reclaim its sacred space.

In the Buddhist tradition, walking the path is as important as reaching the destination. This World Heritage Day, may Uren begin its journey back to light.

(The author is retracing the trails of Xuanzang)